on

George Washington's Money War

How finacne almost lost the Revolutionary War

In September 1778, George Washington was trying to rebuild the Continental Army. The French had just entered the war and three months before, the Americans had just defeated the British at the Battle of Monmouth. Things were looking up. But as the British were on the back foot, another enemy was threatening Washington and his army. More frightening than the shot of the British, the enemy was hyperinflation. Ironically, the man who would eventually be the face of the one dollar bill spent a lot of time worrying about the value of the continental dollar, and how its collapse endangered the American Revolution.

The problem was how to entice the new recruits to join. Several in congress suggested to Washington that they provide him with silver coins to pay new recruits. Washington wasn’t keen on the idea because by 1778, the gap in value between paper continental dollars and specie (gold and silver coins) had widened sufficiently that he worried about the “pernicious consequences” of his existing troops discovering that their paychecks were becoming worthless. “They would cast their views to desertion (at least)”, Washington wrote in a letter. As the young United states started to get a grip on the military situation, they needed to shift their focus to the economic situation that was beginning to spiral out of control.

An issue of paper

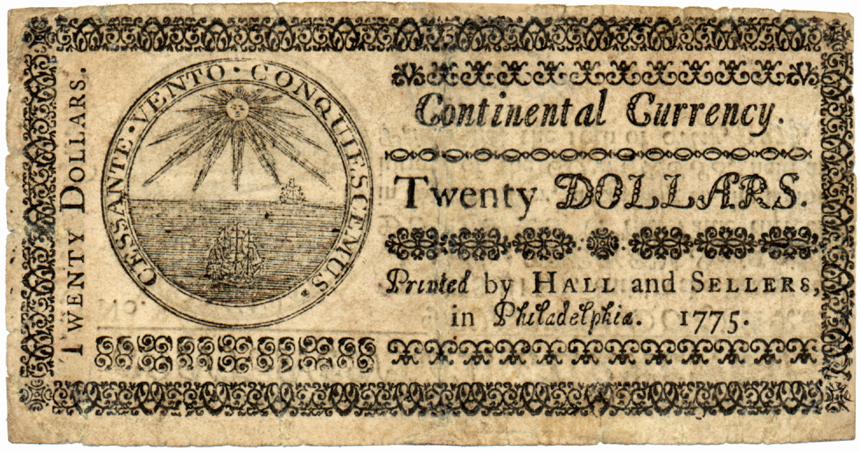

Paper money had been used in the American colonies since the 17th century. Individual colonies would often print paper money in order to maintain the levels of circulating currency when stocks of precious metal coins were depleted through trade. Early on, there were few controls on printing money which sometimes led to hyperinflation and the collapse of these local currencies. The British government passed a series of acts in the mid 18th century putting restrictions on colonial paper currency. These acts restricted how much money colonies could print and when paper money could be used for the payment of debts, both public and private. The purpose of this legislation was to protect merchants from currency depreciation during voyages across the Atlantic. Though, unpopular in the colonies, the currency laws likely had an influence on the perceived acceptability of paper money as a form of payment.

Printing paper continental dollars was the primary way the colonies funded the war. Initially conceived of as promissory notes that were exchangeable for specie at a later date, the continental dollar soon became a de facto fiat currency. The early experiment in a national fiat currency (i.e. currency backed by faith in the issuer alone) lead to what is now predictable hyperinflation. Prices soared and merchants accustomed to British restrictions on paper currency began to refuse payment in continental dollars. The revolutionary leadership began to debate what should be done about the increasingly untenable situation.

Washington, for his part in reenlisting the army, suggested just ignoring the problem for the time being. Although he feared that his troops would desert if they were to find out that their continental dollars were worth much less than equivalent silver, he suggested simply to keep his troops ignorant of that fact. If congress kept paying the army in paper dollars, the troops would be unlikely to know. However, the hyperinflation was known in the wider economy, and there were those in congress that knew ignorance would not be an option for long.

The public debate

In their letters the revolutionary leadership thought hyperinflation to be the work of bad actors. The belief was that certain merchants, whether through greed or through allegiance to the British, were hoarding goods and refusing paper money in order to drive up prices. In their letters American leaders complained bitterly of “Monopolizers, Forestallers, and Engrossers” that were wrecking the economy. Washington goes so far as to call them “Murderers of our cause”. This is unlikely the full story. It makes sense that merchants used to British restrictions on paper currency would be hesitant to accept continental dollars.

Congress and individual colonies tried to tackle the problem by trying to shame people they thought were hoarding or refusing to accept the paper continental dollars. A pamphlet in Boston railing against forestalling and engrossing particularly targeted the merchants from Nantucket for “first introduced the accursed crime of refusing paper money”.

This process of shaming those perceived to be manipulating the economic situation for their own gain follows grass roots attempts to regulate prices, sometimes with violence. In 1775, a mob of women in Boston grabbed a merchant by the neck and threw him into a cart when he refused to sell coffee to the crowd at what they thought was a reasonable price. Similar food riots across new England made women the arbiters of fair prices in the early part of the war.

There were also attempts to prevent the currency’s depreciation through legislation. Afraid that counterfeiting was also contributing to the collapse of the Continental dollar, Pennsylvania passed a law that would see conterfeitters executed or mutilated. In a letter, Washington cheered on these laws, saying that those who sought to profit at the expense of their country be “hunted down as pests to society”. In Washington’s view, taking advantage of the depreciating currency was not just wrong, it was unpatriotic, an existential threat to the revolution.

“a Kind of imperceptible Tax”

The patriotic pressure seemed to work in delaying the complete collapse of the currency until foreign intervention could stabilize the economic situation. While there was significant depreciation, the continental dollar was not entirely worthless. By 1781, the currency had collapsed as a circulating currency. However, The historian Farley Grubb argues that debates over redeeming Continetal Dollars for specie currency continued into the 1790s. By the time the currency collapsed, the military situation had improved for the Americans and French money allowed Congress to pay the army without resorting to printing money. The people who were left holding continental money lost out.

In 1779, Ben Franklin wrote a letter analyzing the continental dollar’s depreciation. He ultimately concludes that, though congress did not intend it to be, the currency and its depreciation was a tax to pay for the war. He figured that because the currency was depreciating so swiftly that its drop in value in the period between when someone receives the money and when they spend it was their contribution to the war effort. Writing this analysis from France, Franklin also points out how European politicians couldn’t fathom how the whole system of paper currency worked. “they don’t understand how we were able to fight a war for four years with no money”[get an exact quote] he wrote. The expedience of paper money that colonies had to adopt because of a lack of money actually turned out to be critical to the colonies winning their independence.

The financial aspects of the American War of Independence are often little considered, but the experiment in American democracy would not have been possible with the experiment in fiat currency.

References

Grubb, Farley, 2008. “The Continental dollar: How Much Was Really Issued?,” The Journal of Economic History, Cambridge University Press, vol. 68(01), pages 283–291, March.

Grubb, Farley, “State Redemption of the Continental dollar, 1779–90,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., vol. 69, no. 1 (Jan. 2012), pp. 147–180.

“From George Washington to Gouverneur Morris, 5 September 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed September 29, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-16-02-0560. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 16, 1 July–14 September 1778, ed. David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006, pp. 528–529.]

“To George Washington from Richard Henry Lee, 5 October 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed September 29, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-17-02-0280. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 17, 15 September–31 October 1778, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008, pp. 267–268.]

“From George Washington to Richard Henry Lee, 23 September 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed September 29, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-17-02-0095. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 17, 15 September–31 October 1778, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008, pp. 97–99.]

“From Benjamin Franklin to Samuel Cooper, 22 April 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed September 29, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-29-02-0298. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 29, March 1 through June 30, 1779, ed. Barbara B. Oberg. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992, pp. 354–356.]

“From Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 July 1775,” Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed September 29, 2019, http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=L17770730aa.

“The Female Food Riots of the American Revolution,” New England Historical Society, accessed September 29, 2019, http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/the-female-food-riots-of-the-american-revolution

Sumner, William Graham. Robert Morris: The Financier and the Finances of the American Revolution. Vol. 2. Cosimo, Inc., 2005.